The Rotten Etymology of Punk (Part 1 of 3)

“Punk” has been used to describe music since at least 1899

As Otto Wise exhaled, one night in the final few months of the nineteenth century, the smoke from his cigar curled towards the ceiling of B’nai B’rith Hall, San Francisco. Wise, a twenty-seven year old attorney, was “director” for that nights’ “smoker” at the fraternal lodge, encouraging attendees to do a turn for the entertainment of the two hundred other guests...

Wise turned next to Eugene Levy, a fellow attorney. Levy, who was thirty nine, sang as requested....

Whatever the song, it was bad. Before Levy could sit down, Wise mocked it. Wise was a consciously cultured man — he gave public lectures on Jewish literature and “the social life of the ghetto” — and this song, he thought, was so bad that it needed a new word, a word that probably hadn’t been used about music before, at least not in print, a noteworthy word, more noteworthy than the song itself. It was, he said that night in October 1899, “the most punk song ever heard in a hall.”

|

| “The most punk song ever heard in a hall,” 1899 (Source: San Francisco Call) |

Many punk historians have tried to capture the complexities of the word “punk.” “Ask forty punk rockers how they define punk and you’ll get forty different answers, and they’ll all be right,” Bob Stanley suggested in Yeah Yeah Yeah: The Story of Modern Pop. It is a “notoriously slippery term,” Nicholas Rombes wrote, in A Cultural Dictionary of Punk, “unstable, ambiguous, loaded with so many suggestions.” According to Richard Cabut, in an introduction to Jon Savage’s ‘Punk Etymology,’ in Cabut and Gallix’s Punk Is Dead: Modernity Killed Every Night, “at the beginning — and at the end — is the word.”

If the story of punk’s etymology is told at all, it is normally told this way: at the very end of the sixties, and the very start of the seventies, the word bubbled up in rock criticism, most notably when Lester Bangs referred to The MC5 and Iggy Pop as “punks.” In 1971, they say, Creem editor Dave Marsh coined the term “punk rock,” in a review of ? And The Mysterians. The next year, the future Patti Smith guitarist Lenny Kaye used the phrase to describe Nuggets, his compilation of mid-sixties garage. By 1976, it was used for the bands who played at Max’s Kansas City and CBGBs, via a New York magazine called Punk. The term re-crossed the Atlantic, and was used to describe London bands....

Those that mention any older history might suggest that Bangs got the word from William Burroughs — who is sometimes quoted to suggest punk meant “someone who took it up the ass” — or that Shakespeare used the word to mean “prostitute.” Any older musical history of “punk” is lost, with only faint smoke trails lingering, through forgotten journalists in regional newspapers, underappreciated female critics and rock crit faves, back to Otto Wise and his cigars, and further still, through centuries.

|

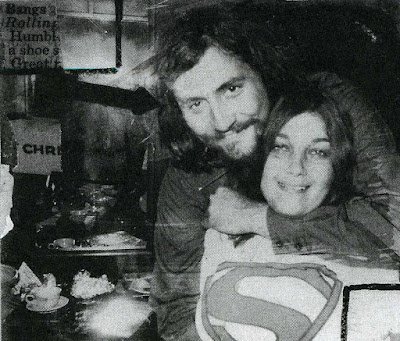

| Lester Bangs and Lillian Roxon (Source: Robert Milliken, Lillian Roxon: The Mother of Rock) |

Punk was already mean and ironic by the time Shakespeare used it. His punks were flashy and transgressive even at the end of the sixteenth century. “This punk is one of Cupid’s carriers,” he wrote, in The Merry Wives of Windsor around 1597. “She may be a punk;” Lucio says in Measure for Measure, “for many of them are neither maid, widow, nor wife.” In All’s Well That Ends Well, the Clown mentions a “taffeta punk” for whom the “French clown” would be “fit.”

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, punk was first printed in 1575, the year Shakespeare became a teenager. It appeared in a song, a ballad called ‘Simon The Old Kinge,’ or sometimes ‘Old Simon The King.’ The song’s narrator suggests that being drunk is “a sin, as it is to keep a punk.” It seems to be a joke, a drinking song disguised as a morality tale, or vice versa. The song was popular, and was reprinted often, becoming a standard for hundreds of years. According to one writer in 1776, it was played drunkenly in taverns, with “half a dozen fiddlers” playing “till themselves and their audience were tired.” Despite its “harsh and discordant tones,” “people thought it fine music.”

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, a new meaning for punk grew, a meaning that had never been used in Britain: punk as rotting wood, used for tinder, and eventually other things that smoulder, like fuses and incense...

Eventually, the word became a standalone adjective, meaning poor quality, and was applied to the arts: there were “punk shows” in theatres in San Francisco by 1889. Newspapers speculated about the word’s origins... Some said it had come from “hoboes,” “passed along thousands of miles of railroad,” or from “our colored brethren,” or noted it was used by young people, complaining about “punk” plays with no “hot stuff in dem.” This seems to be the sense in which Otto Wise used the word in the B’nai B’rith Hall, earning cheap laughs in a well-to-do setting with a youthful, working class word.

Although it was used across America, it seems small-town Kansas was a particular hotbed for early references to “punk” music: there was a “punk orchestra” in Emporia in 1898; a “punky band” paraded down the street in Waverly in 1899, most likely a theatrical group in blackface; Iola had a “punk concert” in 1901, and Hutchinson had a “punk band” in 1902.

By 1901, according to the St Louis Republic, punk was “everyday twentieth century slang.” In 1907, the Los Angeles Times mentioned a campaign for “punk music by union men,” on its front page. In 1908, there was a “punk opera” in Nebraska. “Punk music” was played in New York, by “a man violinist and his wife accompanist,” and in Utah, by a “cross-eyed accordion player.” In 1913, according to the New York Evening Telegram, a woman “an inch deep in make-up and all swathed in violet chiffon veils and chinchilla” sailed across the Atlantic, “strumming on a guitar in the moonlight and humming French songs. Her voice was punk.” At least one vaudeville performer fought a critic over the word’s use. The first cinematic punk appeared in 1916, in Pedro The Punk Poet.

|

| Advertisement for Pedro The Punk Poet, 1916 (Source: Hot Springs New Era) |

The word was used so often, it began to sound like a genre in its own right. “It is little wonder that the managers send us punk music shows,” the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette grumbled in 1914. “These draw audiences of great size, while the sane and intelligent exercise of stage art goes unattended.” According to the Tampa Times in 1917, “the latest war song, ‘Send Me Away With A Smile,’ is very punk and therefore very popular.” “The popularity of a song depends upon its punkness,” the article suggested. “The demand of the day is ‘punk songs for punk people.’”

Read the complete article here.

Read part 2 here.

No comments:

Post a Comment